Model > Estimate > Linear regression (OLS)

(Linear) Regression: The workhorse of empirical research in the social sciences

All example files discussed below can be loaded from the Data >

Manage page. Click the examples radio button and press

Load.

Functionality

Start by selecting a response variable and one or more explanatory variables. If two or more explanatory variables are included in the model we may want to investigate if any interactions are present. An interaction exists when the effect of an explanatory variable on the response variable is determined, at least partially, by the level of another explanatory variable. For example, the increase in price for a 1 versus a 2 carrot diamond may depend on the clarity level of the diamond.

In the Summary tab we can test if two or more variables

together add significantly to the fit of a model by selecting variables

in the Variables to test dropdown. This functionality can

be very useful to test if the overall influence of a variable of type

factor is significant.

Additional output that requires re-estimation:

- Standardize: Coefficients can be hard to compare if the explanatory variables are measured on different scales. By standardizing the response variable and the explanatory variables before estimation we can see which variables move-the-needle most. Radiant standardizes data by replacing the response variable \(Y\) by \((Y - mean(Y))/(2 \times sd(Y))\) and replacing all explanatory variables \(X\) by \((X - mean(X))/(2 \times sd(X))\). See Gelman 2008 for discussion

- Center: Replace the response variable Y by Y - mean(Y) and replace all explanatory variables X by X - mean(X). This can be useful when trying to interpret interaction effects

- Stepwise: A data-mining approach to select the best fitting model. Use with caution!

- Robust standard errors: When

robustis selected the coefficient estimates are the same as OLS. However, standard errors are adjusted to account for (minor) heterogeneity and non-normality concerns.

Additional output that does not require re-estimation:

- RMSE: Root Mean Squared Error and Residual Standard Deviation

- Sum of Squares: The total variance in the response variable split into the variance explained by the Regression and the variance that is left unexplained (i.e., Error)

- VIF: Variance Inflation Factors and Rsq. These are measures of multi-collinearity among the explanatory variables

- Confidence intervals: Coefficient confidence intervals

The Predict tab allows you calculate predicted values from a

regression model. You can choose to predict responses for a dataset

(i.e., select Data from the Prediction input

dropdown), based on a command (i.e., select Command from

the Prediction input dropdown), or a combination of the two

(i.e., select Data & Command from the

Prediction input dropdown).

If you choose Command you must specify at least one

variable and value to get a prediction. If you do not specify a value

for each variable in the model, either the mean value or the most

frequent level will be used. It is only possible to predict outcomes

based on variables in the model (e.g., carat must be one of

the selected explanatory variables to predict the price of

a 2-carat diamond).

- To predict the price of a 1-carat diamond type

carat = 1and press return - To predict the price of diamonds ranging from .5 to 1 carat at steps

of size .05 type

carat = seq(.5,.1,.05)and press return - To predict the price of 1,2, or 3 carat diamonds with an ideal cut

type

carat = 1:3, cut = "Ideal"and press return

Once the desired predictions have been generated they can be saved to

a CSV file by clicking the download icon on the top right of the screen.

To add predictions to the dataset used for estimation, click the

Store button.

The Plot tab is used to provide basic visualizations of the data as well as diagnostic plots to validate the regression model.

Example 1: Catalog sales

We have access to data from a company selling men’s and women’s

apparel through mail-order catalogs (dataset catalog). The

company maintains a database on past and current customers’ value and

characteristics. Value is determined as the total $ sales to the

customer in the last year. The data are a random sample of 200 customers

from the company’s database and has the following 4 variables

- Sales = Total sales (in $) to a household in the past year

- Income = Household income ($1000)

- HH.size = Size of the household (# of people)

- Age = Age of the head of the household

The catalog company is interested in redesigning their Customer Relationship Management (CRM) strategy. We will proceed in two steps:

- Estimate a regression model using last year’s sales total. Response

variable: sales total for each of the 200 households; Explanatory

variables: household income (measured in thousands of dollars), size of

household, and age of the household head. To access this dataset go to

Data > Manage, select

examplesfrom theLoad data of typedropdown, and press theLoadbutton. Then select thecatalogdataset. - Interpret each of the estimated coefficients. Also provide a statistical evaluation of the model as a whole.

- Which explanatory variables are significant predictors of customer value (use a 95% confidence level)?

Answer:

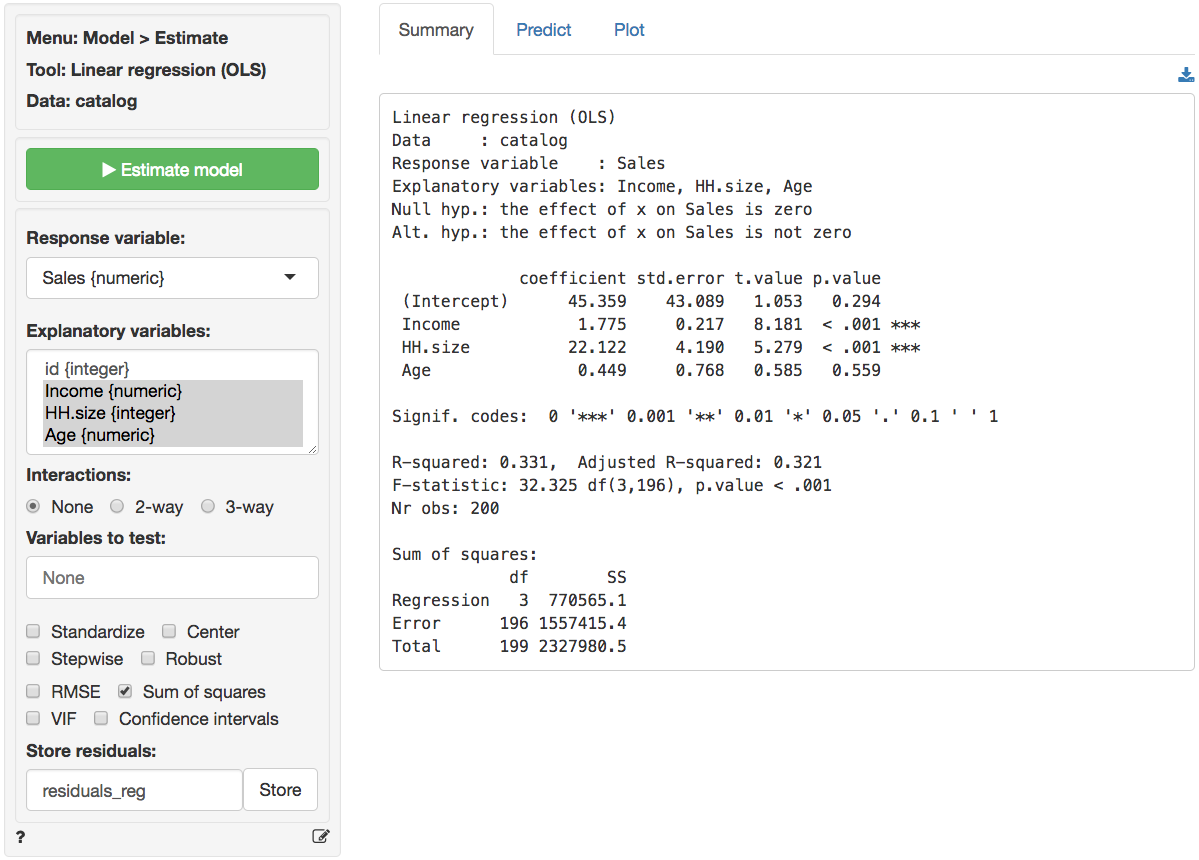

Select the relevant variables mentioned above and press the

Estimate model button or press CTRL-enter

(CMD-enter on mac). Output from Model > Linear

regression (OLS) is provided below:

The null and alternate hypothesis for the F-test can be formulated as follows:

- \(H_0\): All regression coefficients are equal to 0

- \(H_a\): At least one regression coefficient is not equal to zero

The F-statistic suggests that the regression model as a whole

explains a significant amount of variance in Sales. The

calculated F-statistic is equal to 32.33 and has a very small p.value

(< 0.001). The amount of variance in sales explained by the model is

equal to 33.1% (see R-squared).

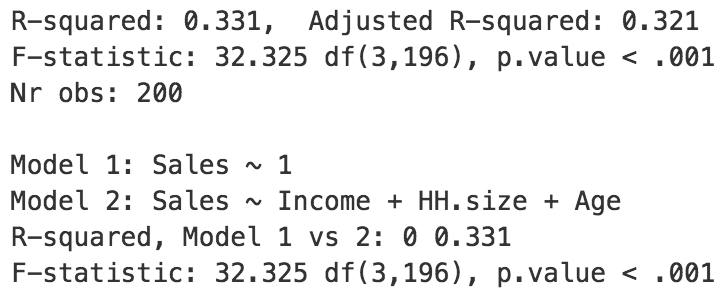

We can replicate the standard F-test that is reported as part of all

regression output by selecting income,

HH.size, and Age in the

Variables to test box. The relevant output is shown

below.

Note that in this example, “model 1” is a regression without explanatory variables. As you might expect, the explained variance for model 1 is equal to zero. The F-test compares the fit of model 1 and model 2, adjusted for the difference in the number of coefficients estimated in each model. The test statistic to use is described below. \(R^2_2\) is the explained variance for model 2 and \(R^2_1\) is the explained variance for model 1. \(n\) is equal to the number of rows in the data, and \(k_2\) (\(k_1\)) is equal to the number of estimated coefficients in model 2 (model 1).

\[ \begin{eqnarray} F & = & \frac{(R^2_2 - R^2_1)/(k_2 - k_1)}{(1 - R^2_2)/(n - k_2 - 1)} \\\\ & = & \frac{(0.331 - 0)/(3 - 0)}{(1 - 0.331)/(200 - 3 - 1)} \\\\ & = & 32.325 \end{eqnarray} \]

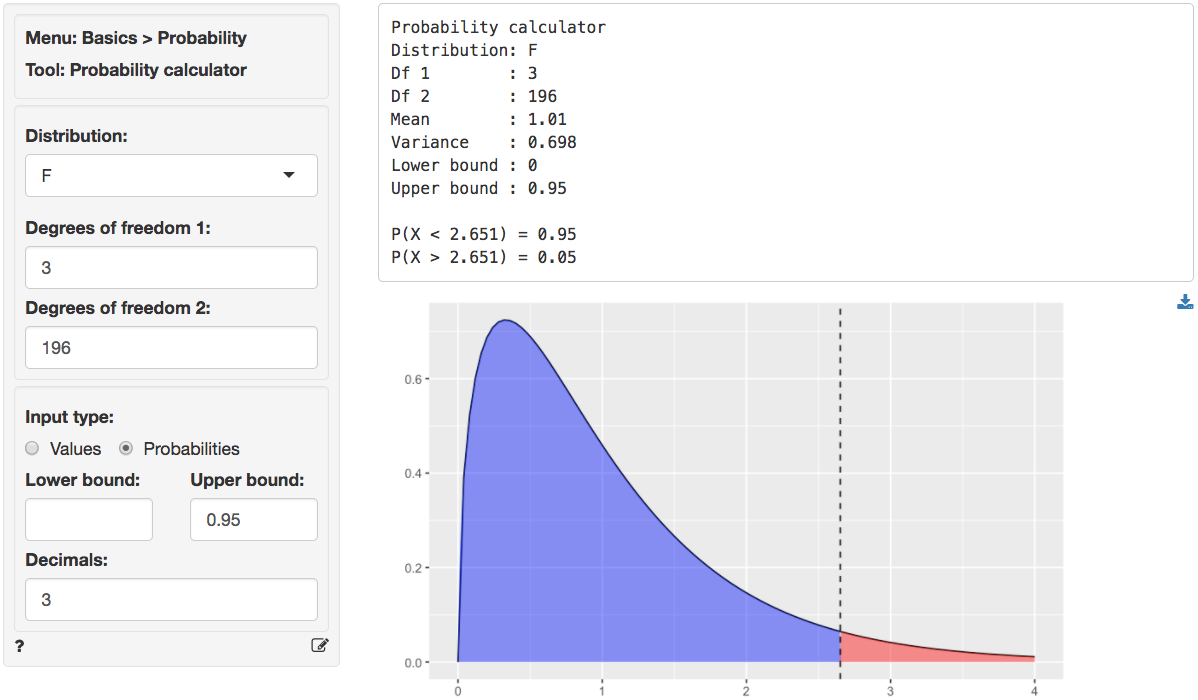

We can use the provided p.value associated with an F-statistic of 32.325 to evaluate the null hypothesis. We can also calculate the critical F-statistic using the probability calculator. As we can see from the output below that value is 2.651. Because the provided p.value is < 0.001 and the calculated F-statistic is larger than the critical value (32.325 > 2.651) we reject null hypothesis that all coefficient are equal to zero.

The coefficients from the regression can be interpreted as follows:

- For an increase in income of $1000 we expect, on average, to see an increase in sales of $1.7754, keeping all other variables in the model constant.

- For an increase in household size of 1 person we expect, on average, to see an increase in sales of $22.1218, keeping all other variables in the model constant.

- For an increase in the age of the head of the household of 1 year we expect, on average, to see an increase in sales of $0.45, keeping all other variables in the model constant.

For each of the explanatory variables the following null and alternate hypotheses can be formulated:

- H0: The coefficient associated with explanatory variable x is equal to 0

- Ha: The coefficient associated with explanatory variable x is not equal to 0

The coefficients for Income and HH.size are

both significant (p.values < 0.05), i.e., we can reject H0 for each

of these coefficients. The coefficient for Age HH is not

significant (p.value > 0.05), i.e., we cannot reject H0 for

Age HH. We conclude that a change in Age of the household

head does not lead to a significant change in sales.

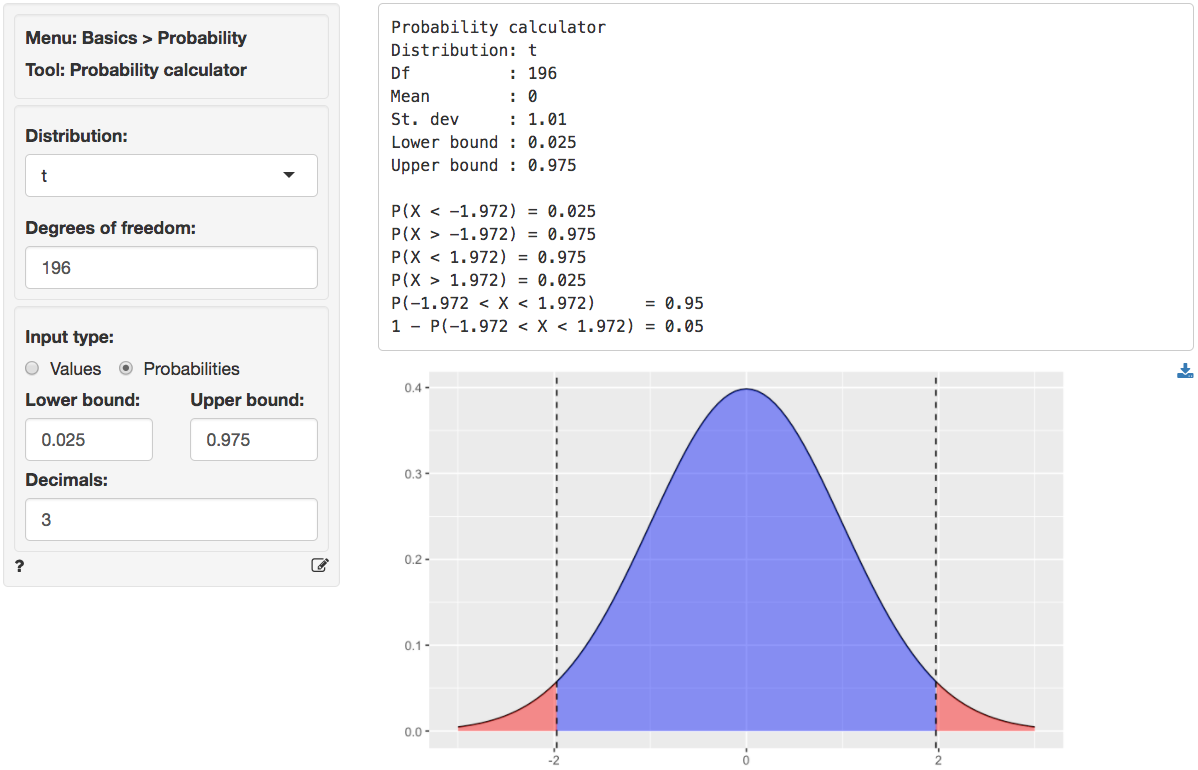

We can also use the t.values to evaluate the null and alternative

hypotheses for the coefficients. Because the calculated t.value for

Income and HH.size is larger

than the critical t.value we reject the null hypothesis for

both effects. We can obtain the critical t.value by using the

probability calculator in the Basics menu. For a t-distribution

with 196 degrees of freedom (see the Errors line in the

Sum of Squares table shown above) the critical t.value is

1.972. We have to enter 0.025 and 0.975 as the lower and upper

probability bounds in the probability calculator because the alternative

hypothesis is two.sided.

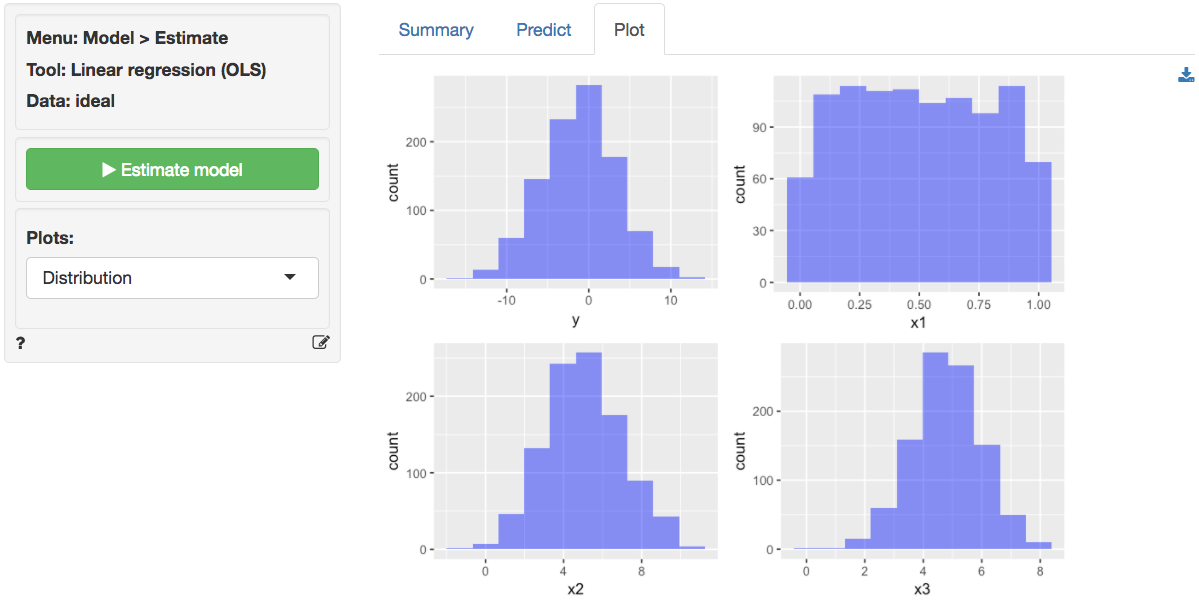

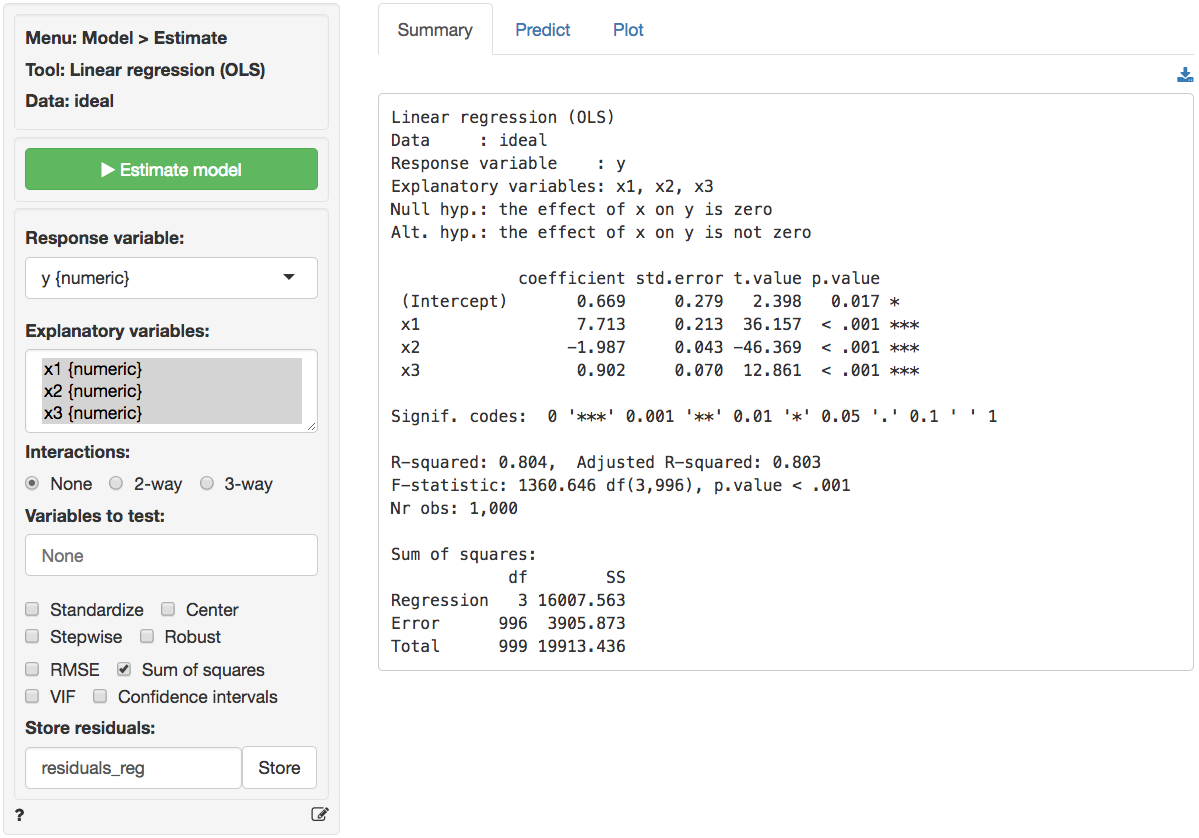

Example 2: Ideal data for regression

The data ideal contains simulated data that is very

useful to demonstrate what data for, and residuals from, a regression

should ideally look like. The data has 1,000 observations on 4

variables. y is the response variable and x1,

x2, and x3 are explanatory variables. The

plots shown below can be used as a bench mark for regressions on real

world data. We will use Model > Linear regression (OLS) to

conduct the analysis. First, go the the Plots tab and select

y as the response variable and x1,

x2, and x3 as the explanatory variables.

y, x2, and x3 appear (roughly)

normally distributed whereas x1 appears (roughly) uniformly

distributed. There are no indication of outliers or severely skewed

distributions.

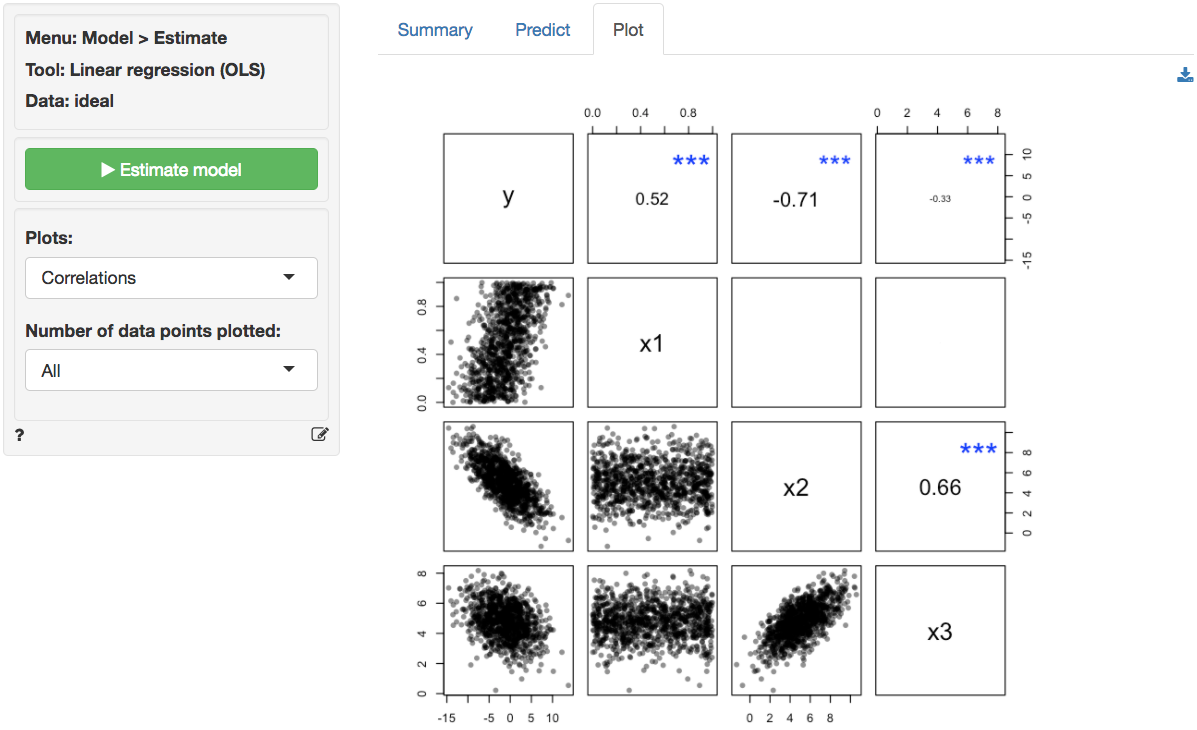

In the plot of correlations there are clear associations among the response and explanatory variables as well as among the explanatory variables themselves. Note that in an experiment the x’s of interest would have a zero correlation. This is very unlikely in historical data however. The scatter plots in the lower-diagonal part of the plot show that the relationships between the variables are (approximately) linear.

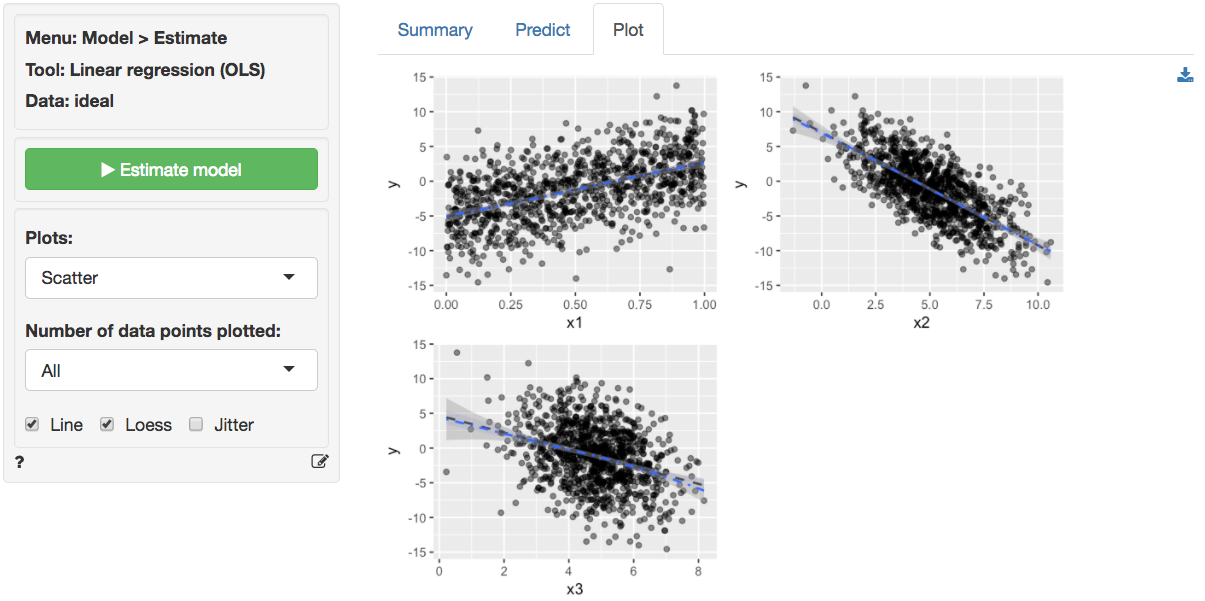

The scatter plots of y (the response variable) against

each of the explanatory variables confirm the insight from the

correlation plot. The line fitted through the scatter plots is

sufficiently flexible that it would pickup any non-linearities. The

lines are, however, very straight, suggesting that a linear model will

likely be appropriate.

The dashboard of six residual plots looks excellent, as we might expect for these data. True values and predicted values from the regression form a straight line with random scatter, i.e., as the actual values of the response variable go up, so do the predicted values from the model. The residuals (i.e., the differences between the values of the response variable data and the values predicted by the regression) show no pattern and are randomly scattered around a horizontal line. Any pattern would suggest that the model is better (or worse) at predicting some parts of the data compared to others. If a pattern were visible in the Residual vs Row order plot we might be concerned about auto-correlation. Again, the residuals are nicely scattered about a horizontal axis. Note that auto-correlation is a problem we are really only concerned about when we have time-series data. The Q-Q plot shows a nice straight and diagonal line, evidence that the residuals are normally distributed. This conclusion is confirmed by the histogram of the residuals and the density plot of the residuals (green) versus the theoretical density of a normally distributed variable (blue line).

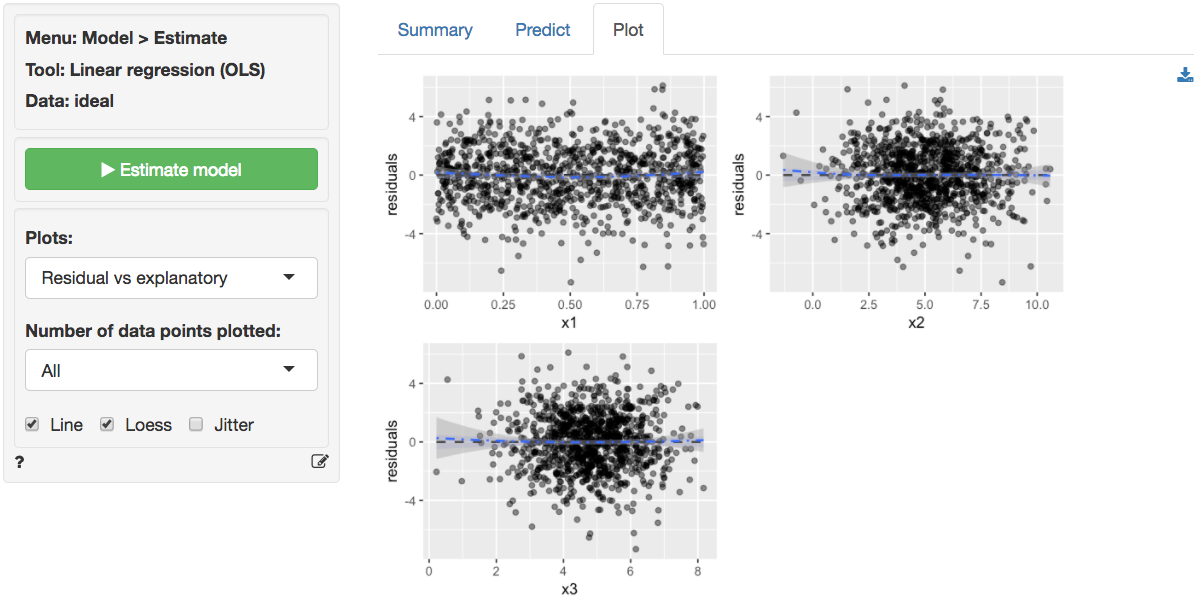

The final diagnostic we will discuss is a set of plots of the residuals versus the explanatory variables (or predictors). There is no indication of any trends or heteroscedasticity. Any patterns in these plots would be cause for concern. There are also no outliers, i.e., points that are far from the main cloud of data points.

Since the diagnostics look good, we can draw inferences from the

regression. First, the model is significant as a whole: the p.value on

the F-statistic is less than 0.05 therefore we reject the null

hypothesis that all three variables in the regression have slope equal

to zero. Second, each variable is statistically significant. For

example, the p.value on the t-statistic for x1 is less than

0.05 therefore we reject the null hypothesis that x1 has a

slope equal to zero when x2 and x3 are also in

the model (i.e., ‘holding all other variables in the model

constant’).

Increases in x1 and x3 are associated with

increases in y whereas increases in x2 are

associated with decreases in y. Since these are simulated

data the exact interpretation of the coefficient is not very

interesting. However, in the scatterplot it looks like increases in

x3 are associated with decreases in y. What

explains the difference? Hint: consider the correlation plots.

Example 3: Linear or log-log regression?

Both linear and log-log regressions are commonly applied to business data. In this example we will look for evidence in the data and residuals that may suggest which model specification is appropriate for the available data.

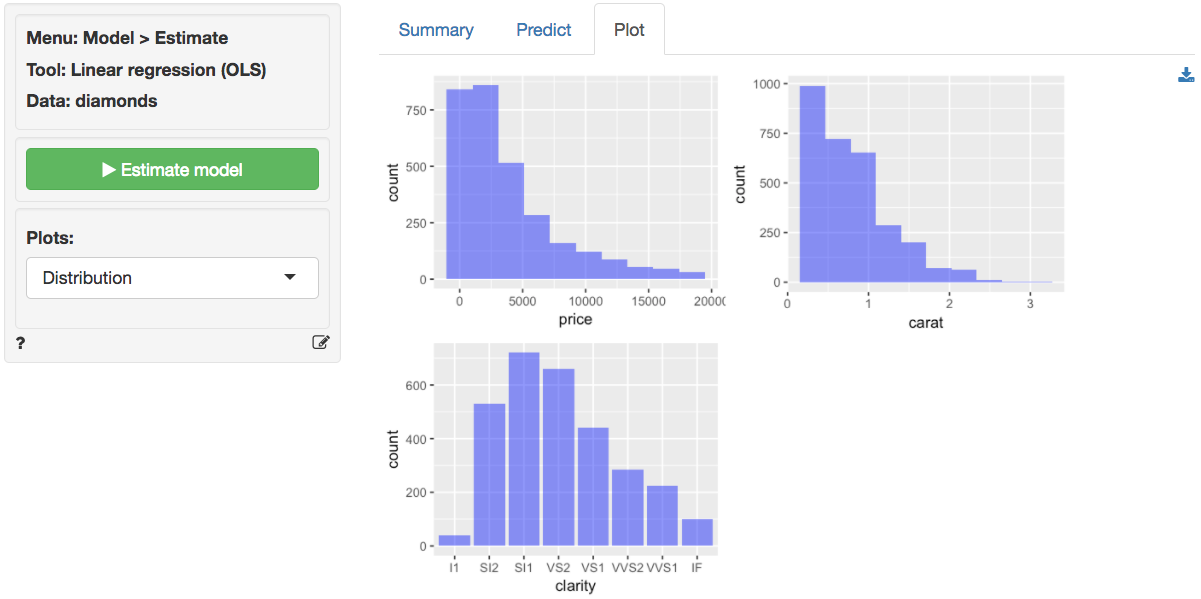

The data diamonds contains information on prices of

3,000 diamonds. A more complete description of the data and variables is

available from the Data > Manage page. Select the variable

price as the response variable and carat and

clarity as the explanatory variables. Before looking at the

parameter estimates from the regression go to the Plots tab to

take a look at the data and residuals. Below are the histograms for the

variables in the model. Price and carat seem

skewed to the right. Note that the direction of skew is determined by

where the tail is.

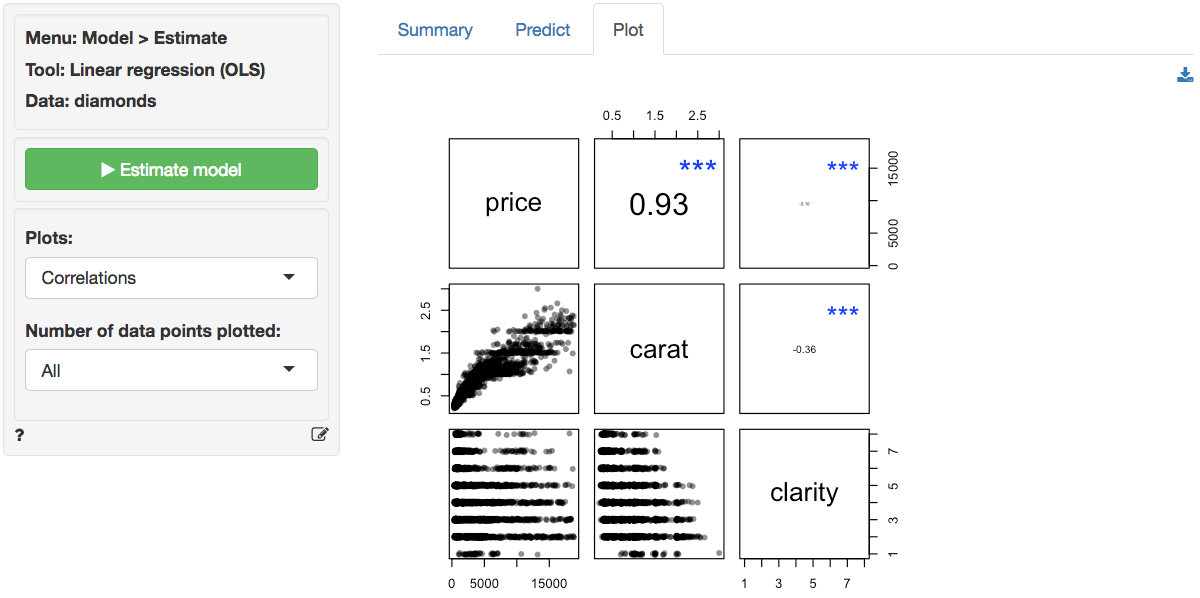

In the plot of correlations there are clear associations among the

response and explanatory variables. The correlation between

price and carat is very large (i.e., 0.93).

The correlation between carat and clarity of

the diamond is significant and negative.

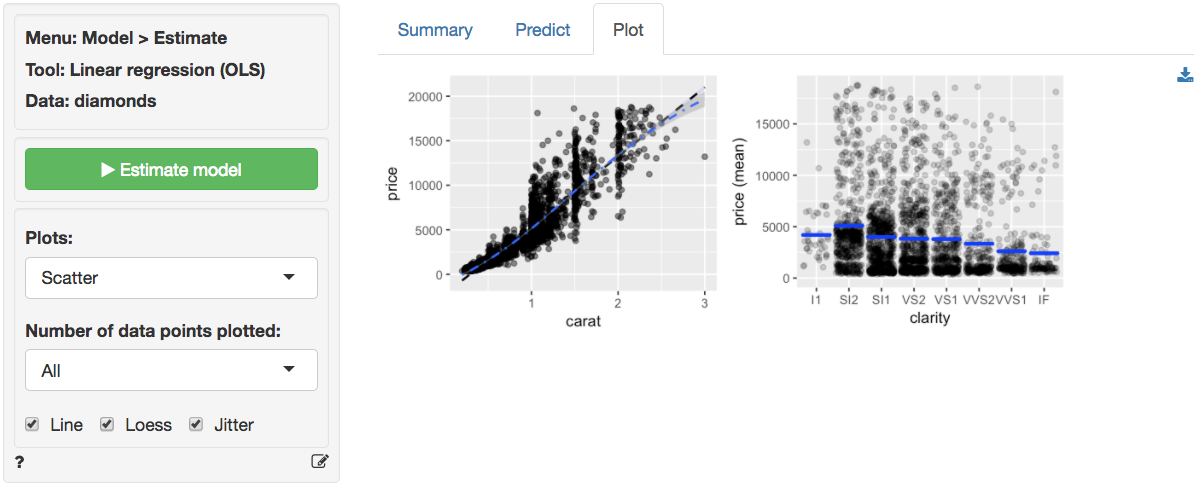

The scatter plots of price (the response variable)

against the explanatory variables are not as clean as for the

ideal data in Example 2. The line fitted through the

scatter plots is sufficiently flexible to pickup non-linearities. The

line for carat seems to have some curvature and the points

do not look randomly scattered around that line. In fact the points seem

to fan-out for higher prices and number of carats. There does not seem

to be very much movement in price for different levels of

clarity. If anything, the price of the diamond seems to go

down as clarity increase. A surprising result we will discuss in more

detail below.

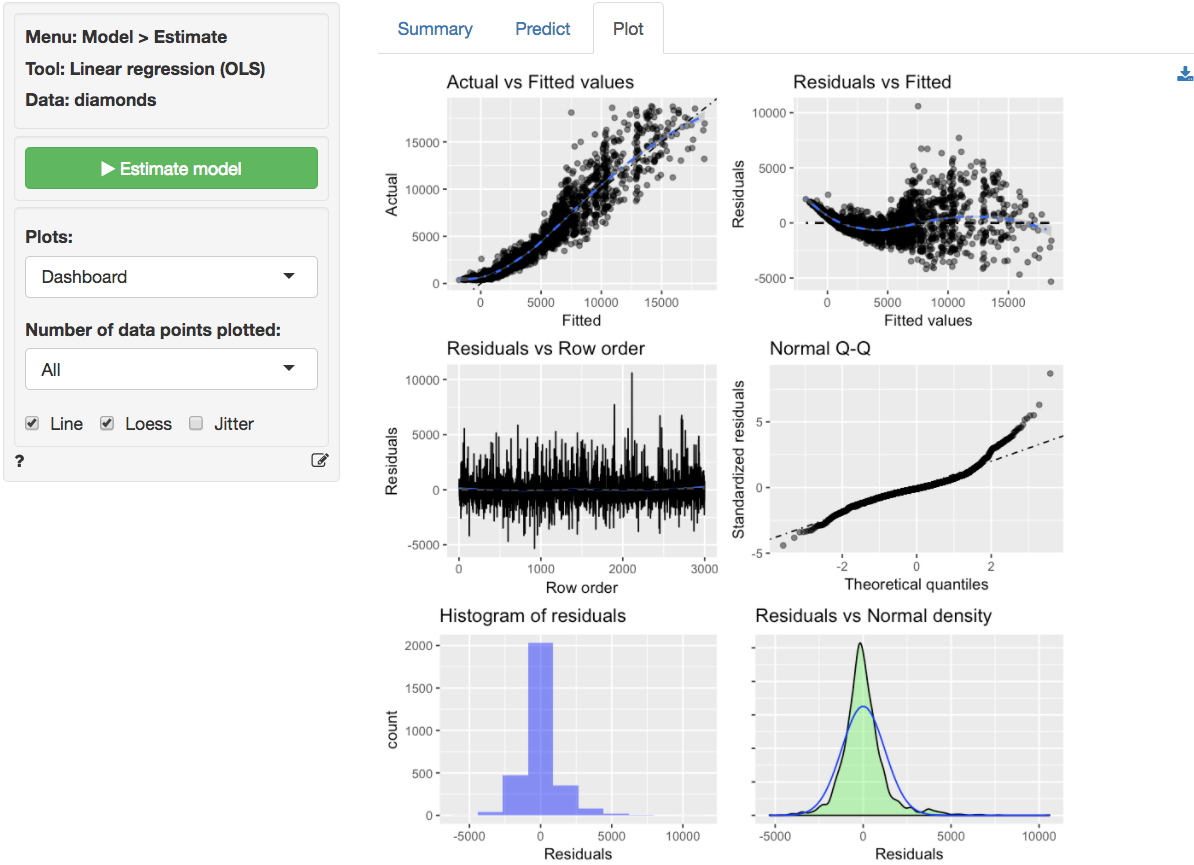

The dashboard of six residual plots looks less than stellar. The true

values and predicted values from the regression form an S-shaped curve.

At higher actual and predicted values the spread of points around the

line is wider, consistent with what we saw in the scatter plot of

price versus carat. The residuals (i.e., the

differences between the actual data and the values predicted by the

regression) show an even more distinct pattern as they are clearly not

randomly scattered around a horizontal axis. The Residual vs Row order

plot looks perfectly straight indicating that auto-correlation is not a

concern. Finally, while for the ideal data in Example 2 the

Q-Q plot showed a nice straight diagonal line, here dots clearly

separate from the line at the right extreme. Evidence that the residuals

are not normally distributed. This conclusions is confirmed by the

histogram and density plots of the residuals that show a more spiked

appearance than a normally distributed variable would.

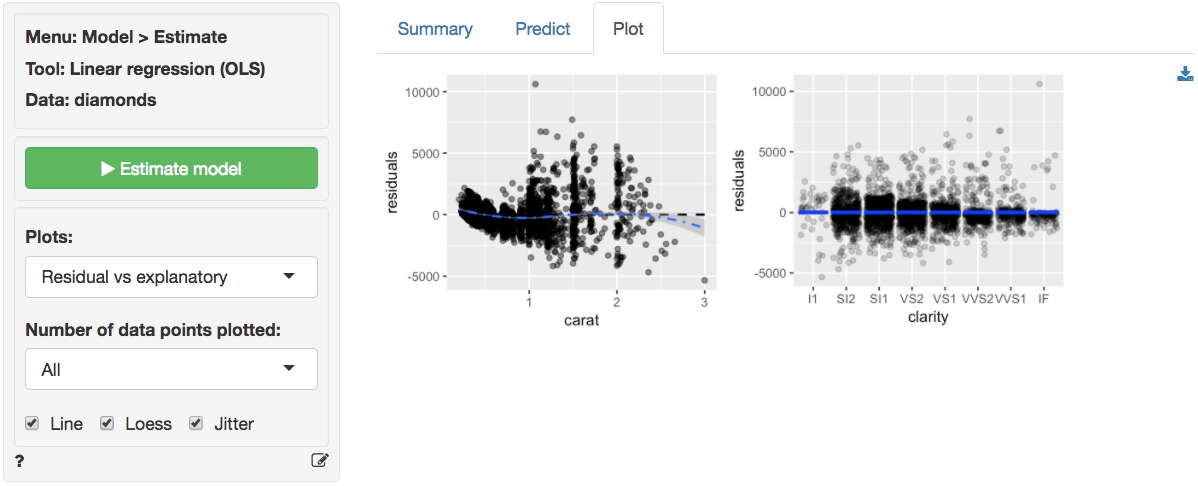

The final diagnostic we will discuss is a set of plots of the

residuals versus the explanatory variables (or predictors). The

residuals fan-out from left to right in the plot of residuals vs carats.

The scatter plot of clarity versus residuals shows outliers

with strong negative values for lower levels of clarity and

outliers with strong positive values for diamonds with higher levels of

clarity.

Since the diagnostics do not look good, we should

not draw inferences from this regression. A log-log

specification may be preferable. A quick way to check the validity of a

log-log model change is available through the Data >

Visualize tab. Select price as the Y-variable and

carat as the X-variable in a Scatter plot.

Check the log X and log Y boxes to produce the

plot below. The relationship between log-price and log-carat looks close

to linear. Exactly what we are looking for!

We will apply a (natural) log (or ln) transformation to both

price and carat and rerun the analysis to see

if the log-log specification is more appropriate for the available data.

This transformation can be done in Data > Transform. Select

the variables price and carat. Choose

Transform from the Transformation type

drop-down and choose Ln (natural log) from the

Apply function drop-down. Make sure to click the

Store button so the new variables are added to the dataset.

Note that we cannot apply a log transformation to clarity

because it is a

categorical

variable.

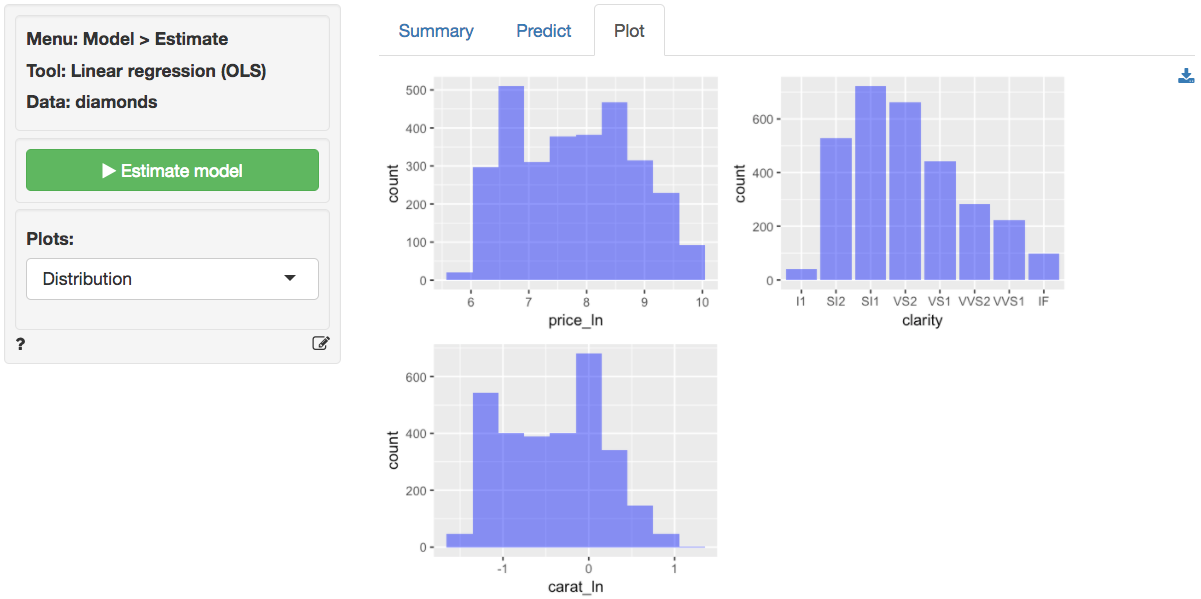

In Model > Linear regression (OLS) select the variable

price_ln as the response variable and carat_ln

and clarity as the explanatory variables. Before looking at

the parameter estimates from the regression go to the Plots tab

to take a look at the data and residuals. Below are the histograms for

the variables in the model. Note that price_ln and

carat_ln are not right skewed, a good sign.

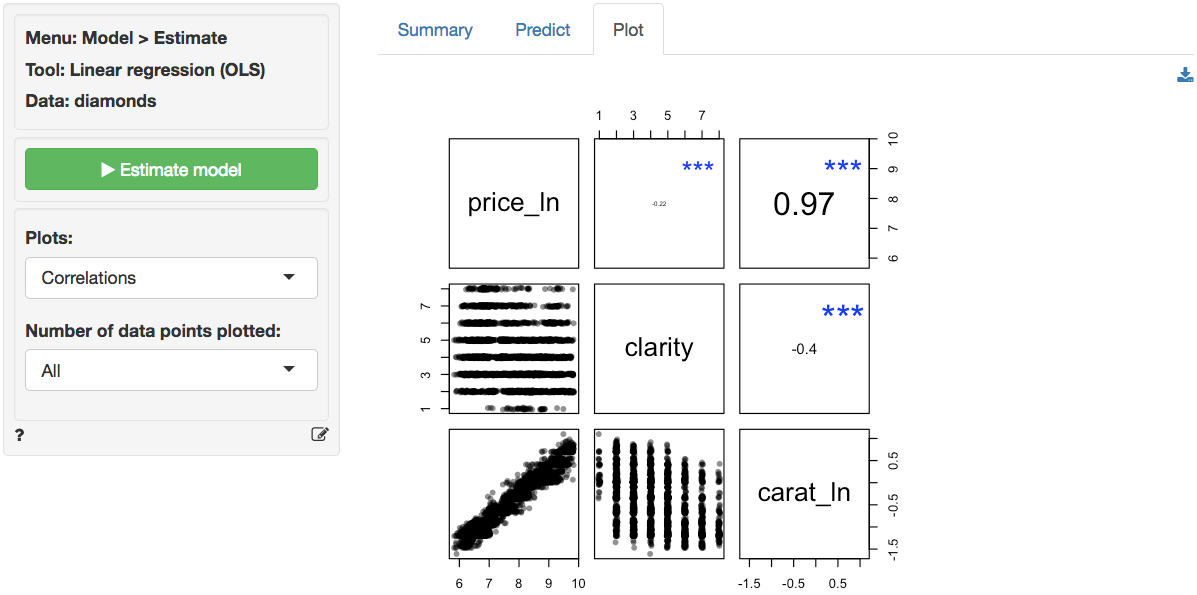

In the plot of correlations there are still clear associations among

the response and explanatory variables. The correlation between

price_ln and carat_ln is extremely large

(i.e., .93). The correlation between carat_ln and

clarity of the diamond is significant and negative.

The scatter plots of price_ln (the response variable)

against the explanatory variables are now much cleaner. The line through

the scatter plot of price_ln versus carat_ln

is (mostly) straight. Although the points do have a bit of a blocked

shape around the line, the scattering seems mostly random. We no longer

see the points fan-out for higher values of price_ln and

carat_ln. There seems to be a bit more movement in

price_ln for different levels of clarity.

However, the price_ln of the diamond still goes down as

clarity increases which is unexpected. We will discuss this

result below.

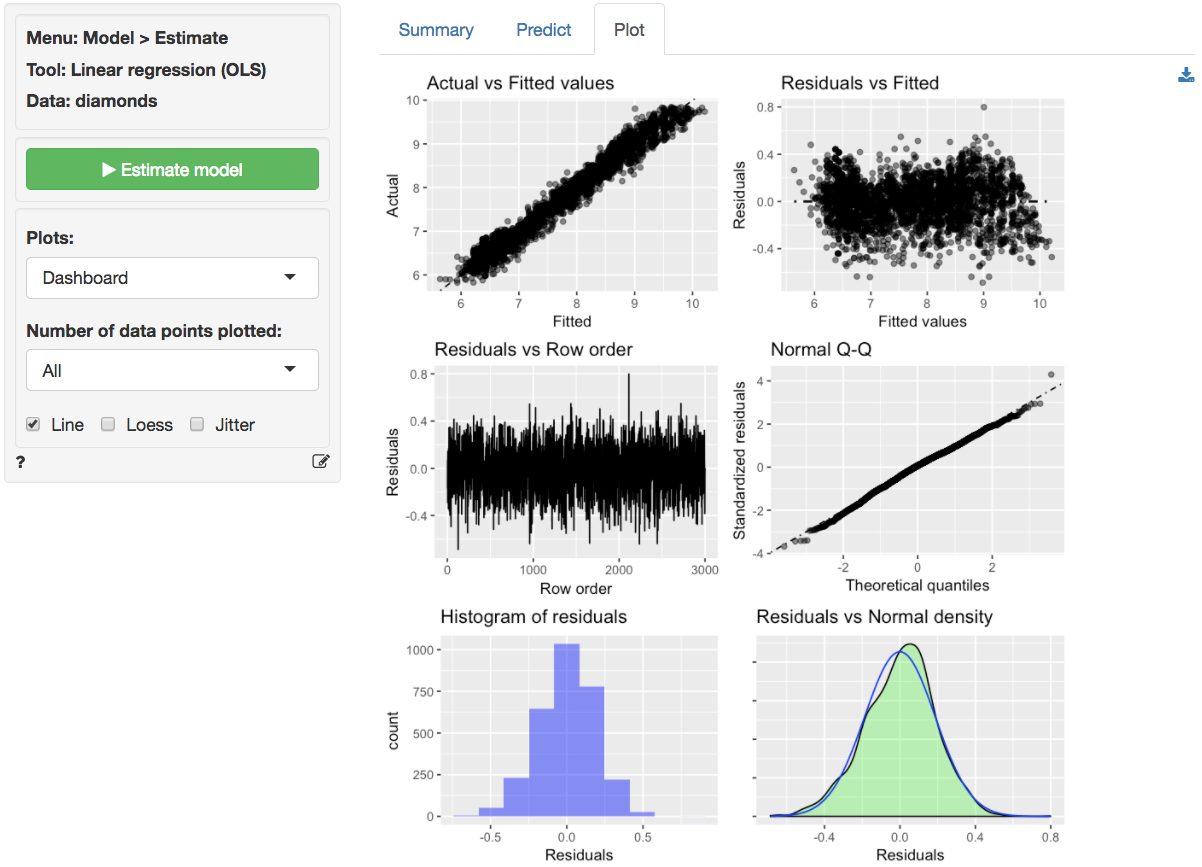

The dashboard of six residual plots looks much better than for the

linear model. The true values and predicted values from the regression

(almost) form a straight line. Although at higher and lower actual and

predicted values the line is perhaps still very slightly curved. The

residuals are much closer to a random scatter around a horizontal line.

The Residual vs Row order plot still looks perfectly straight indicating

that auto-correlation is not a concern. Finally, the Q-Q plot shows a

nice straight and diagonal line, just like we saw for the

ideal data in Example 2. Evidence that the residuals are

now normally distributed. This conclusion is confirmed by the histogram

and density plot of the residuals.

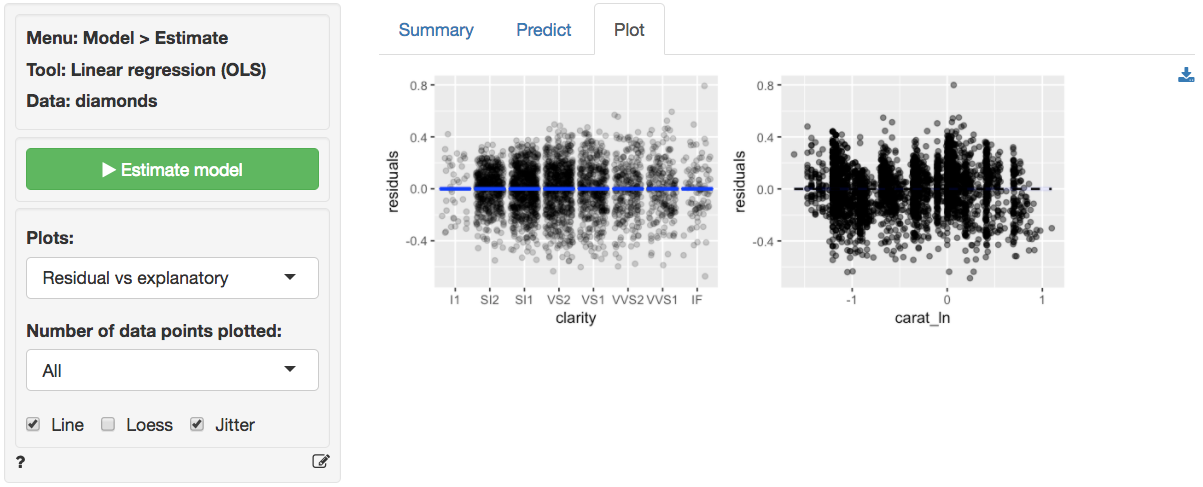

The final diagnostic we will discuss is a set of plots of the

residuals versus the explanatory variables (or predictors). The

residuals look much closer to random scatter around a horizontal line

compared to the linear model. Although for low (high) values of

carat_ln the residuals may be a bit higher (lower).

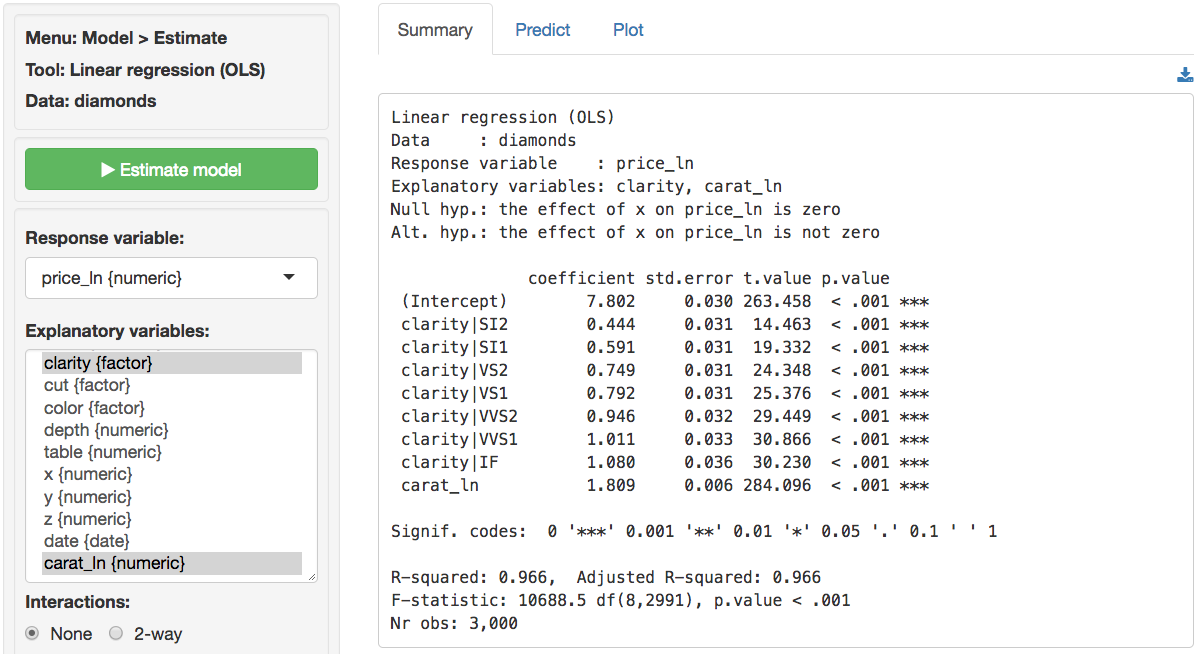

Since the diagnostics now look much better, we can feel more

confident about drawing inferences from this regression. The regression

results are available in the Summary tab. Note that we get 7

coefficients for the variable clarity compared to only one for

carat_ln. How come? If you look at the data description

(Data > Manage) you will see that clarity is a categorical

variables with levels that go from IF (worst clarity) to I1 (best

clarity). Categorical variables must be converted to a set of dummy (or

indicator) variables before we can apply numerical analysis tools like

regression. Each dummy indicates if a particular diamond has a

particular clarity level (=1) or not (=0). Interestingly, to capture all

information in the 8-level clarity variable we only need 7 dummy

variables. Note there is no dummy variable for the clarity level I1

because we don’t actually need it in the regression. When a diamond is

not of clarity SI2, SI1, VS2, VS1, VVS2, VVS1 or IF we

know that in our data it must be of clarity I1.

The F-statistic suggests that the regression model as a whole

explains a significant amount of variance in price_ln. The

F-statistic is very large and has a very small p.value (< 0.001) so

we can reject the null hypothesis that all regression coefficients are

equal to zero. The amount of variance in price_ln explained

by the model is equal to 96.6. It seems likely that prices of diamonds

will be much easier to predict than demand for diamonds.

The null and alternate hypothesis for the F-test can be formulated as follows: H0: All regression coefficients are equal to 0 Ha: At least one regression coefficient is not equal to zero

The coefficients from the regression can be interpreted as follows:

- For a 1% increase in carats we expect, on average, to see a 1.809% increase in the price of a diamond of, keeping all other variables in the model constant

- Compared to a diamond of clarity I1 we expect, on average, to pay 100x(exp(.444)-1) = 55.89% more for a diamond of clarity SI2, keeping all other variables in the model constant

- Compared to a diamond of clarity I1 we expect, on average, to pay 100x(exp(.591)-1) = 80.58% more for a diamond of clarity SI1, keeping all other variables in the model constant

- Compared to a diamond of clarity I1 we expect, on average, to pay 100x(exp(1.080)-1) = 194.47% more for a diamond of clarity IF, keeping all other variables in the model constant

The coefficients for each of the levels of clarity imply that an

increase in clarity will increase the price of diamond. Why

then did the scatter plot of clarity versus (log) price show price

decreasing with clarity? The difference is that in a regression we can

determine the effect of a change in one variable (e.g., clarity) keeping

all other variables in the model constant (i.e., carat). Bigger,

heavier, diamonds are more likely to have flaws compared to small

diamonds so when we look at the scatter plot we are really seeing the

effect of not only improving clarity on price but also the effect of

carats which are negatively correlated with clarity. In a regression, we

can compare the effects of different levels of clarity on (log) price

for a diamond of the same size (i.e., keeping carat

constant). Without (log) carat in the model the estimated effect of

clarity would be incorrect due to

omitted

variable bias. In fact, from a regression of price_ln

on clarity we would conclude that a diamond of the highest

clarity in the data (IF) would cost 59.22% less compared to a diamond of

the lowest clarity (I1). Clearly this is not a sensible conclusion.

For each of the explanatory variables the following null and alternate hypotheses can be formulated: H0: The coefficient associated with explanatory variable X is equal to 0 Ha: The coefficient associated with explanatory variable X is not equal to 0

All coefficients in this regression are highly significant.

Report > Rmd

Add code to

Report

> Rmd to (re)create the analysis by clicking the

icon on the bottom

left of your screen or by pressing ALT-enter on your

keyboard.

If a plot was created it can be customized using ggplot2

commands or with patchwork. See example below and

Data

> Visualize for details.

Video Tutorials

Copy-and-paste the full command below into the RStudio console (i.e., the bottom-left window) and press return to gain access to all materials used in the linear regression module of the Radiant Tutorial Series:

usethis::use_course("https://www.dropbox.com/sh/s70cb6i0fin7qq4/AACje2BAivEKDx7WrLrPr5m9a?dl=1")

Data Exploration and Pre-check of Regression (#1)

- This video shows how to use Radiant to explore and visualize data before running a linear regression

- Topics List:

- View data

- Visualize data

Interpretation of Regression Results and Prediction (#2)

- This video explains how to interpret the regression results and calculate the predicted value from a linear regression model

- Topics List:

- Interpret coefficients (numeric and categorical variables)

- Interpret R-squared and adjusted R-squared

- Interpret F-test result

- Predict from a regression model

Dealing with Categorical Variables (#3)

- This video shows how to deal with categorical variables in a linear regression model

- Topics List:

- Check the baseline category in Radiant

- Change the baseline category

Adding New Variables into a Regression Model (#4)

- This video demonstrates how to test if adding new variables will lead to a better model with significantly higher explanatory power

- Topics List:

- Set up a hypothesis test for adding new variables in Radiant

- Interpret the F-test results

- Compare this F-test to the default F-test in regression summary

Linear Regression Validation (#5)

- This video demonstrates how to validate a linear regression model

- Topics List:

- Linearity (scatter plots, same as the one in the pre-check)

- Normality Check (Normal Q-Q plot)

- Multicollinearity (VIF)

- Heteroscedasticity

- This video demonstrates when and how to run a log-log regression

- Topics List:

- Transform data with skewed distributions by natural log function

- Interpret the coefficients in a log-log regression

Technical notes

Coefficient interpretation for a linear model

To illustrate the interpretation of coefficients in a regression model we start with the following equation:

\[ S_t = a + b P_t + c D_t + \epsilon_t \]

where \(S_t\) is sales in units at time \(t\), \(P_t\) is the price in $ at time \(t\), \(D_t\) is a dummy variable that indicates if a product is on display in a given week, and \(\epsilon_t\) is the error term.

For a continuous variable such as price we can determine the effect of a $1 change, while keeping all other variables in the model constant, by taking the partial derivative of the sales equation with respect to \(P\).

\[ \frac{ \partial S_t }{ \partial P_t } = b \]

So \(b\) is the marginal effect on sales of a $1 change in price. Because a dummy variable such as \(D\) is not continuous we cannot use differentiation and the approach needed to determine the marginal effect is a little different. If we compare sales levels when \(D = 1\) to sales levels when \(D = 0\) we see that

\[ a + b P_t + c \times 1 - a + b P_t + c \times 0 = c \]

For a linear model \(c\) is the marginal effect on sales when the product is on display.

Coefficient interpretation for a semi-log model

To illustrate the interpretation of coefficients in a semi-log regression model we start with the following equation:

\[ ln S_t = a + b P_t + c D_t + \epsilon_t \]

where \(ln S_t\) is the (natural) log of sales at time \(t\). For a continuous variable such as price we can again determine the effect of a small change (e.g., $1 for a $100 dollar product), while keeping all other variables in the model constant, by taking the partial derivative of the sales equation with respect to \(P\). For the left-hand side of the equation we can use the chain-rule to get

\[ \frac {\partial ln S_t}{\partial P_t} = \frac{1}{S_t} \frac{\partial S_t}{\partial P_t} \]

In words, the derivative of the natural logarithm of a variable is the reciprocal of that variable, times the derivative of that variable. From the discussion on the linear model above we know that

\[ \frac{ \partial a + b P_t + c D_t}{ \partial P_t } = b \]

Combining these two equations gives

\[ \frac {1}{S_t} \frac{\partial S_t}{\partial P_t} = b \; \text{or} \; \frac {\Delta S_t}{S_t} \approx b \]

So a $1 change in price leads to a \(100 \times b\%\) change in sales. Note that this approximation is only appropriate for small changes in the explanatory variable and may be affected by the scaling used (e.g., price in cents, dollars, or 1,000s of dollars). The approach outlined below for dummy variables is more general and can also be applied to continuous variables.

Because a dummy variable such as \(D\) is not continuous we cannot use differentiation and will again compare sales levels when \(D = 1\) to sales levels when \(D = 0\) to get \(\frac {\Delta S_t}{S_t}\). To get \(S_t\) rather than \(ln S_t\) on the left hand side we take the exponent of both sides. This gives \(S_t = e^{a + b P_t + c D_t}\). The percentage change in \(S_t\) when \(D_t\) changes from 0 to 1 is then given by:

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac {\Delta S_t}{S_t} &\approx \frac{ e^{a + b P_t + c\times 1} - e^{a + b P_t + c \times 0} } {e^{a + b P_t + c \times 0} }\\ &= \frac{ e^{a + b P_t} e^c - e^{a + b P_t} }{ e^{a + b P_t} }\\ &= e^c - 1 \end{aligned} \]

For the semi-log model \(100 \times \: (exp(c)-1)\) is the percentage change in sales when the product is on display. Similarly, for a $10 increase in price we would expect a \(100 \times \: (exp(b \times 10)-1)\) increase in sales, keeping other variables constant.

Coefficient interpretation for a log-log model

To illustrate the interpretation of coefficients in a log-log regression model we start with the following equation:

\[ ln S_t = a + b ln P_t + \epsilon_t \]

where \(ln P_t\) is the (natural) log of sales at time \(t\). Ignoring the error term for simplicity we can rewrite this model in its multiplicative form by taking the exponent on both sides:

\[ \begin{aligned} S_t &= e^a + e^{b ln P_t}\\ S_t &= a^* P^b_t \end{aligned} \]

where \(a^* = e^a\) For a continuous variable such as price we can again take the partial derivative of the sales equation with respect to \(P_t\) to get the marginal effect.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial S_t}{\partial P_t} &= b a^* P^{b-1}_t\\ &= b S_t P^{-1}_t\\ &= b \frac{S_t}{P_t} \end{aligned} \]

The general formula for an elasticity is \(\frac{\partial S_t}{\partial P_t} \frac{P_t}{S_t}\). Adding this information to the equation above we see that the coefficient \(b\) estimated from a log-log regression can be directly interpreted as an elasticity:

\[ \frac{\partial S_t}{\partial P_t} \frac{P_t}{S_t} = b \frac{S_t}{P_t} \frac{P_t}{S_t} = b \]

So a 1% change in price leads to a \(b\)% change in sales.

R-functions

For an overview of related R-functions used by Radiant to estimate a linear regression model see Model > Linear regression (OLS).

The key functions used in the regress tool are

lm from the stats package and vif

and linearHypothesis from the car package.